Many years ago, I read in Howard Marks’ acclaimed narcotics collection ‘Dope Stories’ that the word ‘assassin’ comes from the 11th Century Islamic terrorist cell ‘Nizari Ismailis’, who used hash before they went on their missions. Ever since then, I have always found the idea of a mashed-up assassin as being particularly excellent.

Recently however, I stumbled across the extensively documented idea that this might not be true. This article aims to bust a myth.

There are many conflicting explanations for where the word ‘hashish’ originates, as during the Crusades, European soldiers found and bastardised many new words. Some oriental scholars argue that the word finds its roots in the Arabic word ‘haschishin’, which means a user of the substance we refer to as hashish today. These scholars believe that in turn, the word ‘haschishin’ not only became ‘hashish’, but also ‘assassin’. Here’s why.

Myth, Mash and Marco Polo.

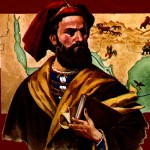

Al-Hassan ibn-al-Sabbah – let’s just call him Hassan shall we – was the head of the 11th Century ‘Persian sect of the Ismailians’, a separatist party of fanatics who in 1090 seized power of the castle of Alamut, just south of the Caspian Sea in modern Iran. The castle of Alamut became Hassan’s stronghold, and from here he trained an army of deadly assassins who gained a huge reputation for their killing efficiency. Hassan became known to visiting Crusaders as the ‘old man of the mountains’ and spread terror in the Mohammedan world until long after his death in 1124. It is widely accepted that in the name of mission success Hassan used some form of intoxicant or sedative to convince his assassins of a world beyond them, and it was this that made them so focussed and determined to follow through their murders. As Marco Polo explained during a visit to Alamut in 1273:

Al-Hassan ibn-al-Sabbah – let’s just call him Hassan shall we – was the head of the 11th Century ‘Persian sect of the Ismailians’, a separatist party of fanatics who in 1090 seized power of the castle of Alamut, just south of the Caspian Sea in modern Iran. The castle of Alamut became Hassan’s stronghold, and from here he trained an army of deadly assassins who gained a huge reputation for their killing efficiency. Hassan became known to visiting Crusaders as the ‘old man of the mountains’ and spread terror in the Mohammedan world until long after his death in 1124. It is widely accepted that in the name of mission success Hassan used some form of intoxicant or sedative to convince his assassins of a world beyond them, and it was this that made them so focussed and determined to follow through their murders. As Marco Polo explained during a visit to Alamut in 1273:

“The old man kept at his court such boys of twelve years old as seemed to him destined to become courageous men. When the old man sent them into the garden in groups of four, ten or twenty, he gave them hashish to drink. They slept for three days, then they were carried sleeping into the garden where he had them awakened.”

“When these young men woke, and found themselves in the garden with all these marvelous things, they truly believed themselves to be in paradise. And these damsels were always with them in songs and great entertainments; they received everything they asked for, so that they would never have left that garden of their own will.“

“And when the old man wished to kill someone, he would take him and say: ‘Go and do this thing. I do this because I want to make you return to paradise’. And the assassins go and perform the deed willingly.”

Stories that the assassins gained powers from their hashish use began to emerge far before Marco Polo was writing. Accounts of their successful assassinations illustrate them as ruthless killers: ‘swift’ and ‘invisible’. Murdering for a right to re-enter paradise, the assassins would stop at nothing to succeed in their missions. But Marco Polo wrote his entry 150 years after Hassan’s death, so can it really be taken as reliable fact?

The followers of Hassan.

It is from stories like Marco Polo’s that the connection between the words ‘hashish’ and ‘assassin’ are made, suggesting that assassin comes from the Arabic word for ‘hashish user’. However, Hassan and his followers spoke ‘Old Persian’- and not Arabic – and so it is now widely recognised that the word assassin comes from ‘Hassassin’, meaning ‘follower of Hassan’. Disappointing.

It is from stories like Marco Polo’s that the connection between the words ‘hashish’ and ‘assassin’ are made, suggesting that assassin comes from the Arabic word for ‘hashish user’. However, Hassan and his followers spoke ‘Old Persian’- and not Arabic – and so it is now widely recognised that the word assassin comes from ‘Hassassin’, meaning ‘follower of Hassan’. Disappointing.

Hassan is also documented as being a strict follower of Islam and a drug and alcohol prohibitionist. This is rather at odds with the idea that he handed out ganja to everyone. Aside from his false paradise – which was the only place where his soldiers were allowed to drink wine – most contemporary scholars believe that hashish was not used to motivate or entrance the assassins, because it would have been against the beliefs of Hassan and extremist Islam to do so.

Other etymological research has also suggested that assassin might come from simple words for ‘enemy’, and in turn, ‘noisy or riotous’, as in the 1930s Egyptian ‘Hashasheen’ meaning the same thing. As Edward Burman states in ‘The Assassins — Holy Killers of Islam’:

“Many scholars have argued, and demonstrated convincingly, that the attribution of the epithet ‘hashish eaters’ or ‘hashish takers’ is a misnomer derived from enemies of the Isma’ilis and was never used by Moslem chroniclers or sources.”

Gutted. It seems that Hassan probably didn’t send out his assassins with an emergency kit of a pipe and a blunt-wrap. Although there are still scholars who would defend this notion, it’s more likely that the drug Hassan used to enduce sleep, before waking his soldiers in ‘paradise’, has been misinterpreted as being a form of hashish. Farhad Daftary, however, author of ‘The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma’ilis’ – believes that the idea of a mashed assassin is not only very unlikely, but detrimental to the preservation of a heritage that is currently misremembered:

“If this propagandist concoction of a ‘stoned’ assassin fails to fit the complex reality of the discipline and training required for committing what was always an explicitly political act, the popular notion of Nizaris as a community of killers also denies their rich, multivalent culture.”

So, some people think that the word assassin comes from hashish, and some think that it comes from enemy, or in basic terms, outcast. Whatever happened, it’s more than likely that there were a group of soldiers living in a castle up a mountain who you definitely wouldn’t fvck with.