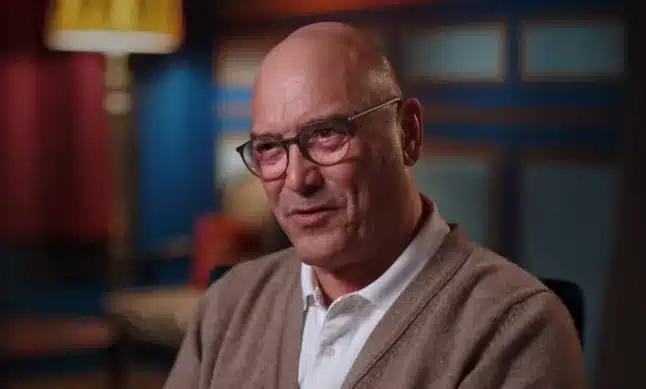

Almost every single minority character in Making A Murderer has been heard from in the past few weeks since its release, and now it’s time to hear from reporter Aaron Keller (pictured above) who was dubbed ‘Silver Fox’ by his fans on the show.

You might remember that he called Ken Kratz out a few times about his conduct during the show, but what’s even more surprising about him is that he was so disillusioned by the verdict in the trial that he actually packed journalism in and started studying to be a lawyer himself. Dean Strang and Jerry Buting even acted as sort of mentors to him as well.

Rolling Stone caught up with him to check out his thoughts not on the case and the TV show and it’s a pretty interesting read. You can check it all out below:

Featured Image VIA

Was covering the Avery trial the thing that ultimately inspired you to go to law school?

It did. Covering this case led to an extreme amount of curiosity about legal processes, and it gave me the confidence that I would be able to grapple with the ideas of the law. I remember, specifically with Avery’s defense team, [developing] an incredible amount of respect for the way they conducted themselves in a very difficult environment. [Dean Strang and Jerry Buting] conducted themselves and behaved as gentleman, even in a contentious environment like that.

Have you spoken to either Buting or Strang since the trial?

At times during law school, I would email Dean and Jerry and ask them questions. There was a question I had, when I was taking my evidence law class, about the admissibility of scientific testing data. I was reading all the critical cases, and I’m like, “That’s not the way the Avery case went down.” So I emailed one of the two and said, “Hey, I’m trying to learn this, but my memory is not jiving with what my textbook says. Is Wisconsin operating outside of the standard protocol?” And I got an email back almost immediately, and they said, “No, you’re recognizing it! Leave it to you to recognize it. Yeah, we do not follow the national standard for the admissibility of scientific testing.”

What does that mean, exactly?

That was part of the whole EDTA testing, and whether or not the test was accurate. In most states, that test probably never would have even been admissible.

Image VIA

Really? Tell me more about that.

Well, under the federal rules of evidence, it’s called the Daubert Standard. Basically, [it means that] scientific testing methods have to be vetted and written about, and the tests have to be examined to see if it’s even valid.

You know, one of the big questions was: Was the blood in the Halbach vehicle planted by the law enforcement community? Because they had that vial of blood, and the blood in the vial had the preservative EDTA in it, and the presumption was that if a test could prove that the blood in the vehicle didn’t have the EDTA, then it couldn’t have been planted from the vial. I believe it was the FBI lab in Quantico that reportedly came up with a test that could distinguish the presence of EDTA, and that was a big issue at the Avery trial. Well, under the Daubert Standard, you can’t just cook up a test. It’s got to be a test that’s been peer-reviewed, and gone through the scientific processes with rigor, and had results duplicated. The test has to be valid. I encourage the people who are upset about this: Read the Daubert case. Rather than sit at home and get all stewed up, and fume about this thing, look at how the rules work.

Is that what you’re doing now: looking at how the rules work?

One of the things that I’m trying to research now, having gone to law school, is: What in the law really, truly led to this decision, and what potential steps need to be considered from here on out?

Wisconsin has since changed that rule, from what I’ve been told. And it was not the result of the Avery case – I believe it was the result of another case. But they have somehow changed their admissibility standard on scientific testing evidence. Is that a move in the right direction? Well, it certainly [gets] them closer [to doing] what the rest of the country’s doing.

Did you ever feel frustrated covering the trial?

The only true emotion I felt through the case was empathy and sadness. Oh, and exhaustion. It was just mentally and physically exhausting to be grappling with this severe and this serious of a set of issues for nearly two years. I mean America has been talking about this [case] for what, a month and a half? Now live with it for two years. We worked on this thing many times seven days a week, 16 hours a day. Those of us who were involved in it, we were not just showing up, punching quotes into the newscast, and going home.

You’re also broadcasting stories of Steven Avery and his attorneys raising ethical questions about the law-enforcement community. You’ve got members of the law-enforcement community watching your TV station. You’ve got the Halbach family watching your TV station. It was exhausting mentally and physically to try to do justice to the facts while also being respectful to those who were being accused or those who were dragged into this unwillingly. That was not easy.

Image VIA

What was it like to cover that first press conference after Brendan Dassey’s confession?

I go down to Calumet County to where they’re having the press conference, and we set up, and the only thing [we know] is just that [there had been] another arrest in the Teresa Halbach case. We had no idea that Ken Kratz was going to sit there and basically, in graphic detail, give his version of the way this went down. The degree of detail that he gave there was honestly a shock to me, to the point that when the thing wrapped up, I went out into the live truck in the parking lot and just sat there with the door closed for about an hour and talked to my parents. It was the single most shocking thing I have ever experienced as a human being, listening to that press conference. I needed to talk to some decent human beings who I love. I called my parents, because I knew I could get a hold of one of them at that time of the day.

And I remember struggling to report it, emotionally. I remember at some point, the next day, calling up at least one of Teresa’s friends and saying, “Are you OK?”

I mean, it was bad. I actually lectured my own law school class about that press conference when I was in law school.

What was that lecture about?

Well, here’s the thing: The general rule in the model rules for professional conduct is that attorneys can’t make statements to the press that would cause material prejudice to a case. Basically it’s a blueprint for almost every law enforcement and prosecutorial press conference everywhere, ever. You can give the name of the accused. Age. Address. You know, identifying information. If there is an active search for someone who is an outstanding suspect, there can be a plea for public health in finding someone.

The American Bar Association writes the model rules. One of the rules says that an attorney can discuss with the press anything that’s on the public record. Ken Kratz – whose professional conduct I called into question on TV after the press conference, and who got madder than heck at me and hung up on me when I had to call him and ask him about it – his response was, “Well, I can talk about anything that’s on the public record.” Well, the problem was, as the prosecutor, he has the power to write up the criminal complaint in the matter, and the criminal complaint is the public record.

Is there other advice you have for people who are upset by this case?

If this case leaves a distaste about the way [things] worked, then the next step is not to sit at home and get all agitated about it and vent, and then look for the next thrill or titillation on film or elsewhere. That’s not the way to respond to this. The way to respond to this is to dig into how the rules operate and to question whether we need another one. That’s the way law works in this country. It is not carved in stone. It is a more fluid system, but it is only a fluid system if we, together, as a society, vow to examine it critically and to change it when change is necessary.

What bothers me the most about the reaction is that people are treating it like it’s a Hollywood thriller, and it’s not. It’s a real-life thing that people struggled very harshly with.

So yeah, basically more reasons why Ken Kratz is a cunt and the legal system in America is totally messed up. Perfect.

If you missed any of our other revelations about Making A Murderer, then check them all out here.